Winners of the Squiggle Experimentation and 80,000 Hours Quantification Challenges

In the second half of 2022, we announced the Squiggle Experimentation Challenge and a $5k challenge to quantify the impact of 80,000 hours' top career paths. For the first contest, we got three long entries. For the second we got five, but most were fairly short. This post presents the winners.

Squiggle Experimentation Challenge

Objectives

From the announcement post:

[Our] team at QURI has recently released Squiggle, a very new and experimental programming language for probabilistic estimation. We’re curious about what promising use cases it could enable, and we are launching a prize to incentivize people to find this out.

Top Entries

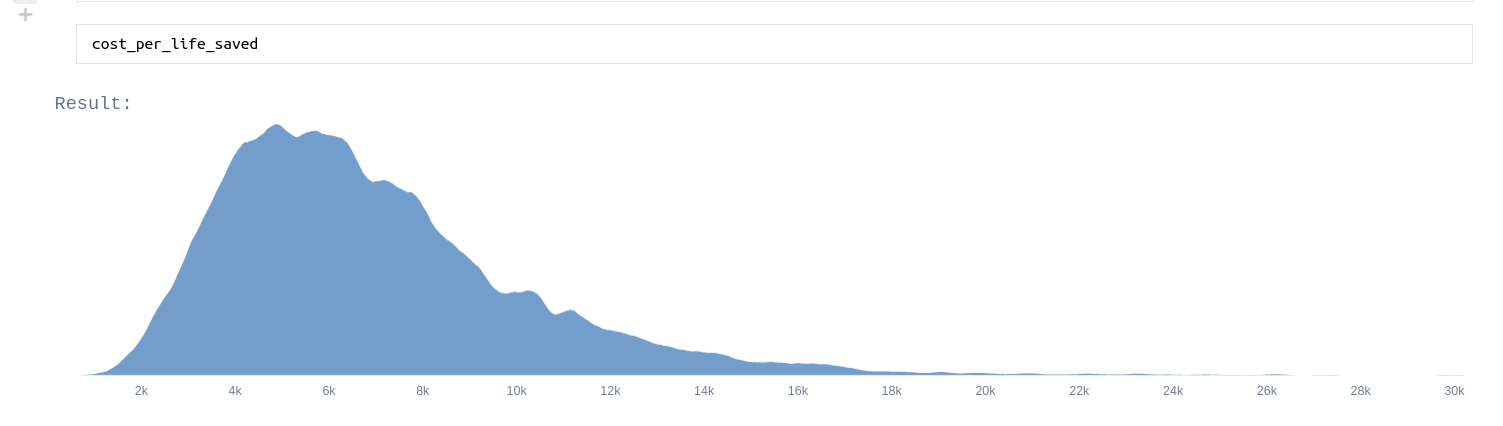

Tanae adds uncertainty estimates to each step in GiveWell’s estimate for AMF in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and ends up with this endline estimates for lives saved (though not other effects):

Dan Wahl’s Cost-effectiveness analysis for the Lead Exposure Elimination Project in Malawi

Dan creates a probabilistic estimate for the effectiveness of the Lead Exposure Elimination Project in Malawi. In the process, he gives some helpful, specific improvements we could make to Squiggle. In particular, his feedback motivated us to make Squiggle faster, first from part of his model not being able to run, then to his model running in 2 mins, then in 3 to 7 seconds.

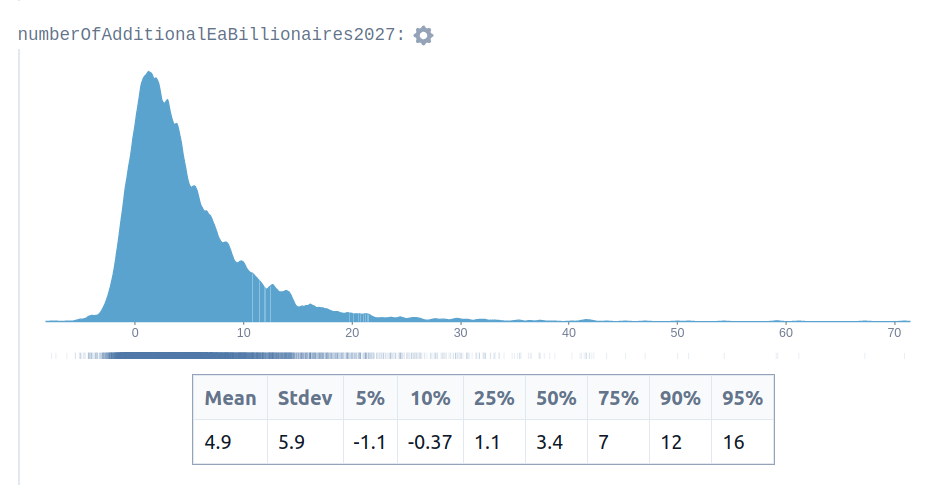

@Erich_Grunewald’s How many EA billionaires five years from now?

Erich creates a Squiggle model to estimate the number of future EA billionaires. His estimate looks like this:

That is, he is giving a 5-10% probability of negative billionaire growth, i.e., of losing a billionaire, as in fact happened. In hindsight, this seems like a neat example of quantification capturing some relevant tail risk.

Perhaps if people had looked to this estimate when making decisions about earning to give, or personal budgeting decisions in light of FTX’s largesse, maybe they would have made better decisions. But it wasn’t the case that this particular estimate was incorporated into the way that people made choices. Rather my impression is that it was posted in the EA Forum and then forgotten about. Perhaps it would have required more work and more vetting to make it actually useful.

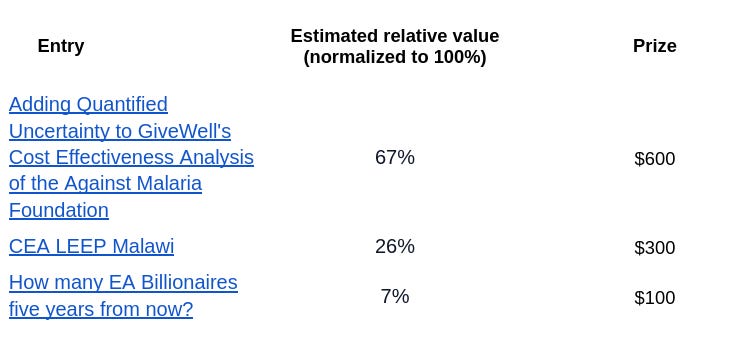

Results

Judges were Ozzie Gooen, Quinn Dougherty, and Nuño Sempere. You can see our estimates here. Per the contest rules, we judged these prizes before October 1, 2022, and winners received their prizes shortly thereafter. Previously I mentioned the results in this edition of the Forecasting Newsletter.

$5k challenge to quantify the impact of 80,000 hours' top career paths

Objectives

With this post, we were hoping to elicit estimates that could be built upon to estimate the value of 80,000 hours’ top 10 career paths. We were also curious about whether participants would use Squiggle or other tools when given free rein to choose their tools.

Entries

@Vasco Grilo’s Cost-effectiveness of operations management in high-impact organisations

Vasco Grilo looks at the cost-effectiveness of operations, first looking at various ways of estimating the impact of the EA community, and then sending a brief survey to various organizations about the “multiplier” of operations work, which is, roughly, the ratio of the cost-effectiveness of one marginal hour of operations work to the cost-effectiveness of one marginal hour of their direct work. He ends up with a pretty high estimate for that multiplier, of between ~4.5 and ~13.

@10xrational’s Estimating the impact of community building work

@10xrational gives fairly granular estimates of the value of various community building activities, in terms of first-order effects of more engaged EAs, and second-order effects of more donations to effective charities and more people working on 80,000 hours’ top career paths. @10xrational ends up concluding that 1-on-1s are particularly effective.

@charrin’s Estimating the Average Impact of an ARPA-E Grantmaker

@charrin looks at the average impact of an ARPA-EA grantmaker, in terms of how much money they have influence over, and what the value of their projects—lowballed as their market cap—is. The formatting was bare-bones, but I thought this was valuable because of the concreteness.

@Joel Becker’s Quantifying the impact of grantmaking career paths

Joel looks at the impact of grantmaking career paths, and decomposes the problem into the probability of getting a job, the money under management, and the counterfactual improvement. He then applies adjustments for non-grantmaking impact, and then translates his numbers to basis points of existential risk averted. A headline number is “a mean estimate of $5.7m for the Open Philanthropy-equivalent resources counterfactually moved by grantmaking activities of the prospective marginal grantmaker, conditional on job offer.”

@Duncan Mcclements’s Estimating the marginal impact of outreach

Duncan fits a standards economics model to estimate the impact of outreach, in R. According to his assumptions, he concludes that

> “these results counterintuitively imply that the current marginal individual would be having substantially higher marginal impact working to expand effective altruism than working on maximising the reduction in existential risk today, with 99.7% confidence”.

Note that 99.7% confidence is the probability given by the model. And one disadvantage of that econ-flavoured approach is that most of the probability of the conclusion going the other way is going to come from model error.

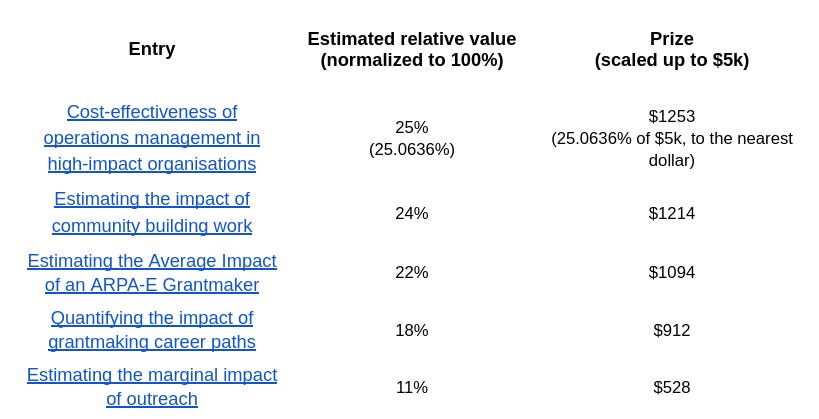

Results

Judges for this challenge were Alex Lawsen, Sam Nolan, and Nuño Sempere. They each gave their relative estimates, which can be seen here, and these were averaged to determine what proportion of the prize each participant should receive. We’ve recently contacted the winners, and they should be receiving their prices in the near future.

With most of these posts, we appreciated the estimation strategies suggested, as well as the initial estimation attempts. But we generally thought that the posts were far from complete estimates, and there is still much work between now and estimating the relative or absolute values of 80,000 hours’ top career paths in a way which would be decision-relevant.

Lessons learnt

From the estimates themselves

From the estimates for the Squiggle experimentation prize, we got some helpful comments that we used to make Squiggle better and faster. I also thought that @Erich_Grunewald’s How many EA billionaires five years from now? was ultimately a good example of quantified estimates capturing some tail risk.

From the entries to the 80,000 hours estimation challenge, we probably underestimated the difficulty of producing comprehensive estimates for 80,000 hours’ top career paths. The strategies submissions proposed nonetheless remain ingenious or valid, and they could be built upon.

On expected participation for estimation prizes

Participation for both prizes was relatively low. This is even though the expected monetary prize seemed pretty high. Both challenges have around 1k views in the EA forum (1139 views for the Squiggle experimentation prize, 1690 views for the 80,000 hours quantification challenge). They were also advertised on the forecasting newsletter, on Twitter, on relevant discords. And for the Squiggle experimentation prize, on the Squiggle announcement post.

My sense is that similar contests with similar marketing should expect a similar number of entries.

Note also that the prizes were organized when EA had comparatively more money, due to FTX.

On judging and reward methods

For the first prize, we asked judges to estimate relative values. Then we converted these to our predetermined prize amounts. I thought that this was inelegant, so for the second prize, we instead scaled the prizes in proportion to the estimated value of the entries.

A yet more elegant method might be to have a variably-sized pot that scales with the estimated value of the submissions. This, for example, does not penalize participants from telling other people about the prize, as a fixed pot prize does. It’s possible that we might try that method in subsequent contests. One possible downside might be that this adds some uncertainty for participants. But that uncertainty can be mitigated by giving clear examples and their corresponding payout amounts.

It remains unclear whether a more incentive-compatible prize design ends up meaningfully improve the outcome of a prize. It might for larger contests, though, so thinking about it doesn’t seem completely useless.